Taking Care of The Flood of Humanity in Bangladesh — 622,000 Rohingya Arrive in Three Months

By Ann Wright

I just returned from Bangladesh, a small country on the Indian sub-continent that has a huge population of 165 million, one-half the population of the United States — in an area the size of Louisiana (50,000 square miles).

Bangladesh deals with annual disastrous typhoons from the Bay of Bengal and the massive floods that routinely submerge large parts of the small country.

The latest flood in Bangladesh is not of water, but of humanity.

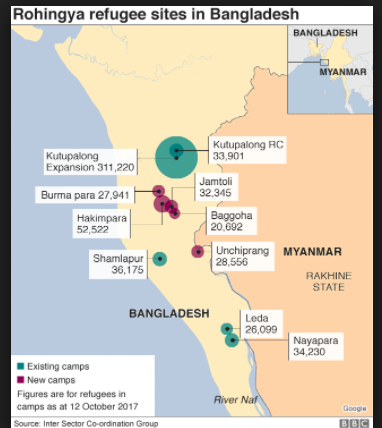

Over 1 million ethnic Rohingya, whose existence has been documented from the 7th century in the Rakhine province of Myanmar, have fled into a very small area of neighboring Bangladesh, on the peninsula south of the city of Cox Bazar, to escape the murderous actions of the Myanmar military that has burned villages, raped and murdered men, women, children, the elderly in the most horrible ways. The Rohingya are Muslim while the dominant religion of Myanmar is Buddhism. Rohingya were not given citizenship of Myanmar by the 1982 citizenship act passed during the reign of the military government. They are considered Bangladeshi migrants, not as citizens of Myanmar.

Endless Sea of Shelters

Shelters on the Terraced Hillsides

In the humanitarian spirit of those with the least helping those with the least, the Bangladesh government has not turned away the flood of Rohingya refugees. Bangladesh’s Prime Minister Sheikh Hasani has famously said, “We are a country of 165 million, we can provide shelter for another 1 million in need.” And they are doing exactly that!!

I went to Bangladesh with the Malaysian NGO MYCare. MYCare has humanitarian projects in 22 countries and is partnering with a Bangladesh NGO, the Allama Faizullah Foundation as a part of the international effort to provide food and supplies to the huge number of Rohingya refugees.

OB/GYN Dr. Fauziah from Malaysia; Beatrice, Midwife from Italy; Yuki, surgeon from Japan.

Dr. Fauziah Hasan, an OB/GYN physician who was the medical doctor recently on the 2016 Women’s Boat to Gaza, was assessing medical needs in the Rohinyga refugee camps, particularly for women. Refugee camp administrators are estimating that between January and August 2018, 70,000 women will give birth in the refugee camps. Dr. Fauziah brought with her portable ultra sound equipment that she used in the mobile clinics with which she worked. Other members of the MY Care mission were Ummu Fatima Al Zaaraf Zulkifli and Ariej Basri who have done refugee work with Syrian refugees in Jordan.

On our first day, we visited the Kutupalong refugee camp. It is an incredible scene of an endless sea of bamboo structures with plastic roofs and sides in an ocean of humanity. Hillsides have been terraced to provide space for rows of shelters. But, with the monsoon rains in July and August, a sea of mud will be sliding structures and people down the hills.

The distribution site where we worked was an open-air structure with only a roof next to a shelter that served as a school. We arrived as the morning school session for girls was letting out. Two little girls with blue backpacks emerged from the school and we asked if we could go with them to their homes.

Young school girls with blue backpacks coming from morning school.

Young school girls with blue backpacks coming from morning school.Six women of various ages ranging from an older grandmother figure, two middle aged women and three younger women emerged from the kids’ home shelter. The younger three were pregnant. They told of male members of their families being killed by Myanmar military forces. Three of the women are tailors and would like to begin a sewing business in the camps if they had access to sewing machines. MYCare plans to set up a Women’s Center which would have sewing machines for use by the women.

Women Who Want to be Tailors at the Camp.

Women Who Want to be Tailors at the Camp.That morning, our MYCare mission distributed 500 food packages each with 20 Kilograms of food-rice, cooking oil, potatoes, onions, chilies and turmeric. Another day MYCare distributed another 500 hygiene kits containing a blanket, bed mat, cooking pot and mosquito net.

Hygiene kit distribution.

As Dr. Fauziah said, “It’s a drop in the sea compared to all the needs, but if many contribute drops, then we build a lake.” As we were at one distribution point, a group of Bangladeshi businessmen from a large pharmaceutical company arrived with a donation of 10,000 blankets and 100,000 kilos of rice! Big drops will fill up the lake faster!

Blind woman and two of four children.

MYCare gave a solar light to this woman with four kids under the age of 10. The father was killed. The mother has gone blind so the kids help her with all the work and to the outdoor latrines. Dr. Fauziah and Dr. Siraj will assist the woman to see an ophthalmologist to determine if anything can be done about her sight. MYCare has purchased 400 solar lanterns for distribution — a small number considering the need, but every light at night helps.

The big water truck was donated by the Islamic center in Colon, Panama.

As you can imagine, keeping lines of thousands of people in an orderly fashion without chaos is a major task! The Bangladesh military is in charge of security and through distribution in coordination with the UN agencies and other agencies.

It’s a massive effort to help a massive number of people! And every donation large or small is deeply appreciated.

Ten hospitals have been constructed in the area around the refugee camps. The Malaysian government erected a 50-bed field hospital in less than a week which became operational on November 28. Medical practitioners said that child malnutrition is severe. The elderly, which they classify as anyone over age 50, have chronic diseases and many have limited mobility which makes getting them to the mobile medical clinics difficult.

Rohingya refugees whose medical condition is so severe that they cannot be treated by the medical clinics in the refugee camps are transported to one of the five private hospitals in Cox Bazar. We visited one of those hospitals, the Central hospital, the 40-bed facility with emergency and operating rooms, is supported by the Allama Faziullah Foundation. Once the condition has been treated, the refugee is returned to the camp.

Cox Bazar, a city of 50,000 and an hour away from the camps, is the logistical hub for humanitarian assistance organizations sending food, medicines and construction materials to the refugee camps. The Bangladeshi military is in charge of the security of the camps. They have designated the camps open for International workers from 8am-5pm. As there is virtually no electricity in the camps and with darkness setting in around 5pm, international aid workers depart with darkness. Every now and then one spots a solar panel on the plastic roof of a shelter that may provide limited light for a family at night.

The Bangladesh military controls the camps in all aspects — security, food distribution, and assists UNHCR with family registration that uses up-to-date cellular phone APPs to identify the location of an individual family’s shelter and records the number of people in the family, provides a photo of those in the family and designates a locator number for the shelter, all of which is used to record food, medical and other logistics services. The system is definitely “big brother” on steroids but necessary for allocation of services and documentation for possible return to Myanmar and a claim of citizenship.

Within the cities/camps of refugees, all sorts of commerce is happening. Bangladesh villagers who live in the area have created a huge market on the main road leading into the camps. Rohingya refugee merchants buy from the local merchants and then sell chickens, eggs, fruits, vegetables and assorted candies and chips inside the camps. If you were lucky enough to have brought money with you from Myanmar, there is food to buy; if you have no money you must rely on international food donations.

Large trucks laden with huge quantities of bags filled with food and cooking materials, blankets, mosquito netting, cooking utensils maneuver on the narrow dirt filled roads barely missing kids that are running everywhere.

Lines of people are in every direction. As in every refugee camp I’ve ever visited — Somalia, Sierra Leone, Afghanistan, Pakistan — one of the main features of camp life is standing in line for something and these camps are no exception.

Looking across the Naf River to Myanmar where Rohingya villages were burned and people murdered.

On another day, we drove to the end of the peninsula to look from Bangladesh to Myanmar across the river Naf near the town of Teknaf. In August and September 2017, people were standing on the same cliff watching across the river the Rohingya villages burn and hearing the gun fire that was killing people. While we were standing on the cliff, a small boy named Abbas came up to us.

Dr. Siraj, Abbas and Dr. Fauziah Hasan.

Through our guide and interpreter from the Allama Fazlullah Foundation, Dr. Siraj, an ethnic Rohingya who fled to Bangladesh in 1992 and who has subsequently gotten Bangladesh citizenship, Abbas told us that he had only been in Bangladesh only three days. He said two of his brothers had been killed by the Myanmar military. He, his mother and father fled to Bangladesh by boat with his remaining two brothers.

Agreement with Myanmar

An agreement was reached in November between the governments of Bangladesh and Myanmar for the return of Myanmar residents who fled the violence from October 19, 2016 to the present time. Over 620,000 fled in the three-month period after August 25, 2017.

The agreement calls for the return of documented residents of Myanmar to their own households and original places of residence, or to a safe and secure area near their location of choice. There is no restriction on the number of persons to be repatriated. The assistance of UNHCR will be sought. Myanmar will implement the recommendations of the Kofi Annan report. Refugees will be initially housed in temporary housing requested from India and China.

However, Rohingya with whom we talked in the camps expressed strong distrust of the agreement and the intentions of the Myanmar military. One person said that giving the decision on determining if a person is a resident Myanmar to the Myanmar military is ludicrous as it’s the military that burned the villages, raped and murdered Rohingya forcing one million to flee for their lives.

Another person said that he would like to go back to his home, but if he is forced to live in a camp in Myanmar until a decision is taken that he can go back to his home, he didn’t trust that the Myanmar military would follow through.

As an indication of how the Myanmar military feels about the return of the Rohingya, Myanmar’s Commander-in-Chief of Military Forces Senior General Min Aung Hlang said the Rohingya cannot return to Rakhine province until “real Myanmar citizens” are ready to accept them. “Emphasis should be placed on the wish of the local Rokhine people who are real Myanmar citizens.”

Nobel Peace Laureate and Myanmar State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi has refused to condemn the military’s massacre and burning of villages leading to worldwide condemnation.

Myanmar Commander-in-Chief of Military Forces Senior General Min Aung Hlang and Nobel Peace Laureate Aung San Suu Ky

International aid personnel with whom I spoke are planning for programs in the refugee camps for many months, if not years. The probability of refugees wanting to return to their burned out villages and to a military that by its actions continues to force Rohingya to flee is virtually non-existent. The United Nations or some entity of the international community would have to provide on-the-ground protection before they would return.

Over 200,000 Rohingya remain in refugee camps in Bangladesh from the 1992 exodus from Myanmar, giving support to the theory that hundreds of thousands more Rohingya will decide to remain in Bangladesh rather than risking returning to Myanmar.

In June 2012, after another time of intra-ethnic killings and village burnings in the province of Arakan with the military and police doing nothing to stop it, the President of Myanmar Thein Sein said in a nationwide address that the “only solution” would be to expel the Rohingya to other countries or to camps overseen by the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) — undoubtedly a reference to UNHCR camps in Bangladesh. “We will send them away if any third country would accept them,” Thein Sein said. “This is what we are thinking is the solution to the issue.” The UNHCR quickly rejected the proposal, saying, “As a refugee agency we do not usually participate in creating refugees.”

During the conference on Islamic Thought and Civilization at which I spoke before coming to Bangladesh, former Malaysian Ambassador to the United Nations and President of the United Nations General Assembly Tan Sri Razali Ismail, predicted that the “final solution” of the Rohingya is underway. He said that only 300,000 Rohingya remain in Myanmar. Over 600,000 have fled to Bangladesh in the past three months. He predicted that, despite international attention and pressure, the Myanmar military will continue its slaughter of the Rohingya to force the remaining 300,000 to leave. He predicted that international organizations such as the UN or ASEAN will not intervene. While there is outrage in the international citizenry, organizations are unwilling to break their rules — one negative vote by China in the UN Security council prevents a Chapter 7 UN peace-making mission and Myanmar’s negative vote in ASEAN prevents the deployment of an ASEAN peace-making mission.

WHAT CAN WE DO?

First, urge our respective governments to support the budget of the United Nations organizations such as UN High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR), the UN International Child Education Fund (UNICEF), the World Food Program (WFP), The World Health Organization (WHO), International Organization on Migration (IOM), organizations that provide the bulk of materials used for shelters and the basic food stuffs for all of the Rohingya camps.

Second, make individual donations to the UN agencies or to smaller organizations, such as MYCare of Malaysia, the HOPE Foundation and Save the Children that have important maternal health, hygiene and water programs.

According to UNICEF, UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and Save the Children data there are 5,549 unaccompanied children in the camps.

Third, volunteer (if you have the skills) — We met international humanitarian workers from around the world — from South Korea, Detroit Michigan, Japan, Iceland, Italy, Algeria. Including the Minister of health from Iceland! And, of course, our Malaysian delegation from MYCare! The Japanese medical group has been here for many months and rotates every three weeks. The Italian midwife that is here will be here for two months. They both work at the Red Cross hospital.

Fourth, put pressure on Congress to condemn the Myanmar genocide on the Rohingya.

Ann Wright is a 29-year US Army/Army Reserves veteran, a retired United States Army colonel and retired U.S. State Department official, known for her outspoken opposition to the Iraq War. She received the State Department Award for Heroism in 1997, after helping to evacuate several thousand people during the civil war in Sierra Leone. She is most noted for having been one of three State Department officials to publicly resign in direct protest of the 2003 Invasion of Iraq. Wright was also a passenger on the Challenger 1, which along with the Mavi Marmara, was part of the Gaza flotilla. She served in Nicaragua, Grenada, Somalia, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, Sierra Leone, Micronesia and Mongolia. In December, 2001 she was on the small team that reopened the US Embassy in Kabul, Afghanistan. She is the co-author of the book “Dissent: Voices of Conscience.” She has written frequently on rape in the military.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.